Defect of the Month

Back to AGR's Library

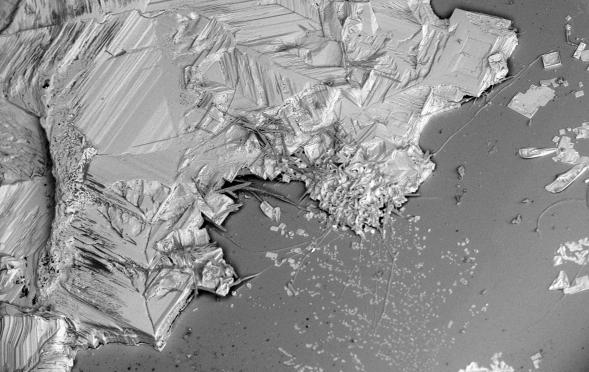

Identifying contaminants in a glass container can be very challenging due to the sheer number of possibilities. Dirt, batch materials, lubricants, packaging, product residues, and organic matter can fall into or be deposited in a bottle during processing. Some contaminants occur relatively frequently, such as mold dope and iron oxide dust. Others can leave an analyst scratching his or her head as to how the substance could possibly have ended up in a container. This SEM micrograph shows a large salt crystal (NaCl) that formed due to evaporation of a liquid in the bottom of a bottle. The original source of the liquid could not be identified, but the lack of damage to the underlying glass indicates that the salty liquid was not introduced while the bottle was extremely hot during or soon after forming.

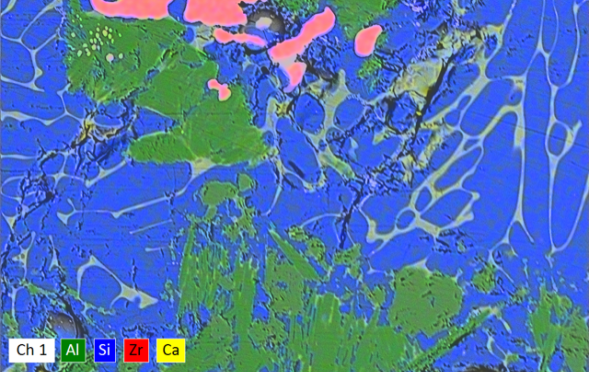

This image bears a striking resemblance to a weather radar map. In reality it is an EDX spectral map conveys a huge amount of information by portraying each element in a particular color. The different areas are portions of a stone found in a glass container that have partially melted or recrystallized. This particular stone resulted in glassy areas (blue and yellow) that separated into calcium-rich and calcium-depleted phases. The red area is composed primarily of zirconia (ZrO2) and the green area is composed of alumina (Al2O3) with magnesia (MgO). The magnesium and zirconia are not found in the bulk glass composition, indicating that the stone likely originated from a refractory source.

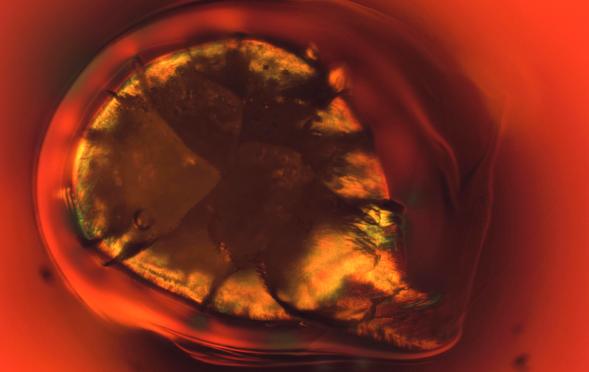

It’s May, the official start of the summer grilling season when backyard grills will be fired up across America. This particular image of a stone in glass resembles a grilled chicken breast slathered in barbeque sauce – although maybe we’re just a little hungry. In any case, the colorful fringe around the stone consists of feathery nepheline crystals (Na2O·Al2O3·2SiO2), which were created by an aluminosilicate refractory stone dissolving in the surrounding glass. Aluminosilicate, or mullite, type refractories are most commonly used in the forehearths of container glass furnaces. The surface cracks around the stone are caused by high stresses due to differences in the coefficient of thermal expansion between glass and refractory materials.

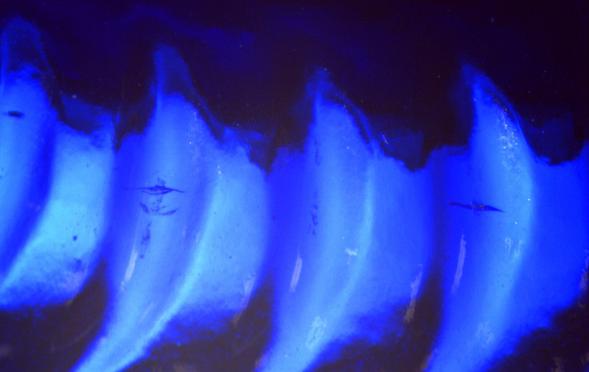

In this magnified view of a cobalt-colored bottle, a series of individual knurls are partially illuminated as large blue crescents. The smaller, vertical cracks running through two of the knurls are flaws referred to as “bearing surface checks.” Bearing surface checks are most often created when rough handling causes damage to the bottom soon after bottle formation. This damage is then extended into checks due to thermal stresses caused by temperature differences between the glass and the transfer or conveyer surfaces. Bearing surface checks may lower the performance of a container subjected to loads such as impact, internal pressure, and thermal shock.

Pagination

- Previous page

- Page 5

- Next page